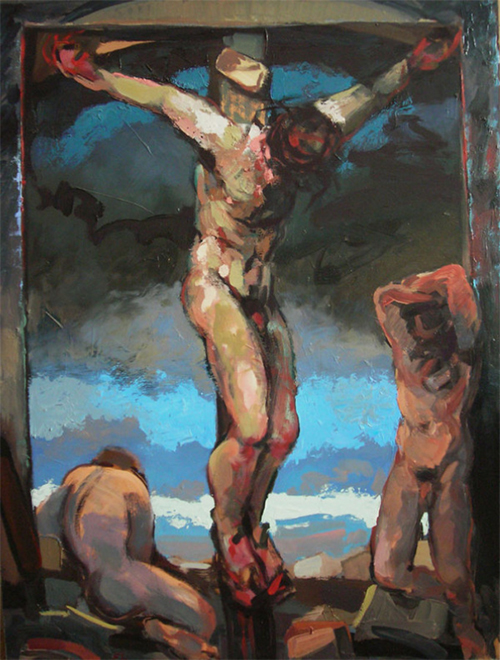

The 16thC Spanish mystic St John of the Cross has a particular image in his book titled The Dark Night of the Soul:

Intimacy with God and with each other will only take place, he says, when we reach a certain kindling temperature.

For too much of our lives, he suggests, we lie around as damp, green logs inside the fire of love, waiting to come to flame but never bursting into flame because of our dampness.

At first, the fire acts on the wood by driving out all its moisture. Very slowly, it expels from the wood everything that is inconsistent with fire’s nature. It then starts to burn on the outside until, at last, it transforms the wood into fire.

This process of drying is something that, at first, we resist.

However, we begin to recognize its benefits in producing in us a greater conformity to God. John writes, “the whole of our spiritual life can be seen as a preparation for the soul to receive more deeply the love of God.

And, in the same way that a dry log catches fire more easily than a wet one, so the soul responds more immediately to the impulse of God the more prepared it is by the Holy Spirit.”

St. John suggests that we undergo this transformation through the pain of loneliness, restlessness, disquiet, anxiety, frustration, and unrequited desire. In the torment of incompleteness, our psychic temperature rises so that eventually, we come to a kindling temperature, and there, we finally open ourselves to union in new ways.

It is, I suggest, an image for our Advent time.

Advent is about a “holy longing”, about getting in touch with this longing, about heightening it, about letting it raise our psychic temperatures, about sizzling as damp, green logs inside the fires of intimacy, about intuiting the kingdom of God by seeing, through desire, what the world might look like if a Messiah were to come and, with us, establish justice, peace, and unity on this earth.