I am conscious in my own life of how this season and experience of Advent and Christmas can feel like a ‘historical repeat’. I have celebrated many Advents and Christmases, and much has been/is a repeat of previous years.

Like the season of Easter, much time is taken with the preparation of liturgies.

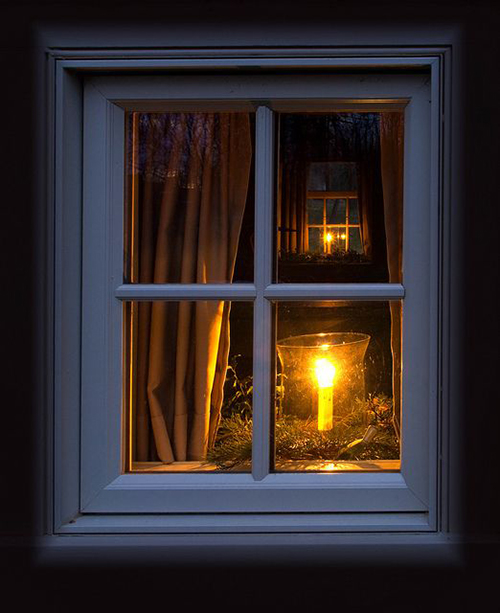

These liturgies take place both in our Churches and at our homes.

In this rush pausing to stop, look, and listen can be overlooked.

At the centre of our Christmas celebration is the recalling that “Christmas declares the glory of the flesh”. This the wonderful opening line from the poem ‘Christmas and the Common Birth’ by the British poet Anne Ridler (1912 – 2001).

When I take time to stop, look, and listen, I realize that the reality of this truth, that ‘Christmas declares the glory of the flesh’, is strongly affirmed in the lexicon of Christian art.

The frequency with which the newborn Jesus is painted naked declares loudly that what we celebrate is indeed the ‘glory of the flesh’.

As we have declared for many, many years, “ Et incarnatus est de Spiritu Sancto, ex Maria virgine; et homo factus est.”

“And [he] was incarnate by the Holy Spirit, of the Virgin Mary; and was made man.”

This is evidenced most dramatically in the altarpiece by the Flemish painter Hugo van der Goes.

The painting, part of a triptych depicting the Adoration of the Shepherds forms part of the Portinari Altarpiece, c. 1476, has every person richly garmented except for? – you guessed right, “The Word made Flesh”. The artwork now hangs in the Uffizi Gallery, in Florence