A line from this Sunday’s First Reading, reads

“for my house shall be called a house of prayer for all peoples”. (Isaiah 56:7)

A recent Saturday evening Mass at Sagrada Familia parish in Barcelona had all the hallmarks of a neighbourhood worship service, from prayers for ill and deceased members to name-day wishes for two congregants in the pews.

But it also featured security checks to get in and curious tourists peering down to take photos of the worshippers from above.

The regular Mass is held in the crypt of modernist architect Antoni Gaudí’s masterpiece church, The Basílica i Temple Expiatori de la Sagrada Família, one of Europe’s most visited monuments.

With the pandemic stringent rules now relaxed, iconic sacred sites are struggling to accommodate the faithful who come to pray and the millions of visitors who often pay to view the art and architecture.

An increasingly popular strategy is to have visitors and the faithful go separate ways – with services held in discrete places, visits barred at worship times, or altogether different entry queues.

This spring, the Vatican opened a separate “pathway” starting outside St. Peter’s Basilica for those who want to enter to pray or attend Mass, so they wouldn’t be discouraged by sometimes hours-long lines for the average of 55,000 daily visitors.

But the challenge remains: how to balance the churches’ competing roles amid the tourism surge without sacrificing their spiritual purpose.

With an estimated 330 million people visiting religious sites yearly around the world, it’s one of the tourism market’s largest segments.

Filled with masterpieces from Romanesque sculpture to lavish Baroque decorations, Santiago’s cathedral of Santiago de Compostela attracts hundreds of thousands of tourists and pilgrims who since the Middle Ages have travelled along the Camino routes to venerate St. James’s tomb.

As people, we need the transcendent.

Leisure and rest, and time with God, are not incompatible,

Co-existence between worshippers and tourists has been controversial at Istanbul’s Hagia Sophia. Built as a landmark cathedral in the Byzantine era, turned into a mosque by the conquering Ottoman empire in the 1400s, and opened as a museum for the last century, it was converted back into a functioning mosque in 2020 by Turkey’s Islamic-oriented government.

Now visitors can tour the structure for free outside of prayer hours. In Hagia Sophia’s main section where prayers are held, the vast mosaics depicting Christian figures are hidden behind drapes and most of the marble floor is covered with carpeting.

With some 2.5 million annual visitors, Barcelona Cathedral was also close to a breaking point. The cathedral instituted caps on visitor numbers, required tour groups to use wireless audio guides to reduce noise, and added staffers to explain the new policies to visitors and those coming for daily Mass or confession, held in a side chapel with crystal doors to preserve silence.

Many of these iconic buildings are still active places of worship.

In a statement it reminds persons visiting that “this cathedral has been and is a space dedicated to prayer” before describing its stunning Catalan Gothic architecture.

3.7 million tourists explored the Sagrada Familia’s arresting architecture and mesmerizing stained glass windows last year. Each begins their visit as a tourist, they may well leave to continue their journey as a pilgrim.

“for my house shall be called

a house of prayer for all peoples”. (Isaiah 56:7)

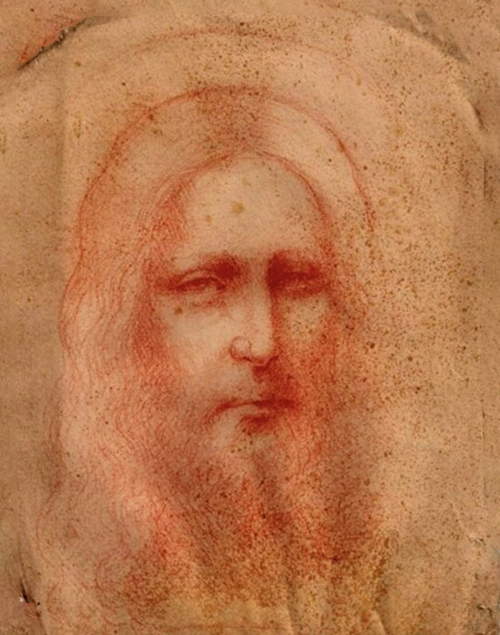

The illustration is of The Cathedral of the Holy Cross and Saint Eulalia, also known as Barcelona Cathedral, Spain.

[It is worth knowing that the building known as the Barcelona Cathedral and the La Sagrada Familia Basilica are separate buildings.]