Billy O’Leary was seven and lived in a very small village miles from anywhere and anyone.

The village had a general store which sold just about everything, a small school, and a small Church.

Billy’s father was the teacher at the school, the only teacher, so Billy used to say his father was the Headteacher.

One day, Billy’s father had to travel to the city for business reasons and invited Billy to travel with him.

Billy was excited for two reasons; he had heard his parents talk of the city and yet had no idea where it was, and second, it meant travelling on the train, which Billy had never done.

The day arrived, and Billy presented himself at breakfast in his Sunday best. He and his father walked to the train station and duly caught the train.

Billy sat by the window and watched cows and sheep and corn and maize go whizzing by.

When his father had finished his business, he asked Billy if there were anything he would like to do.

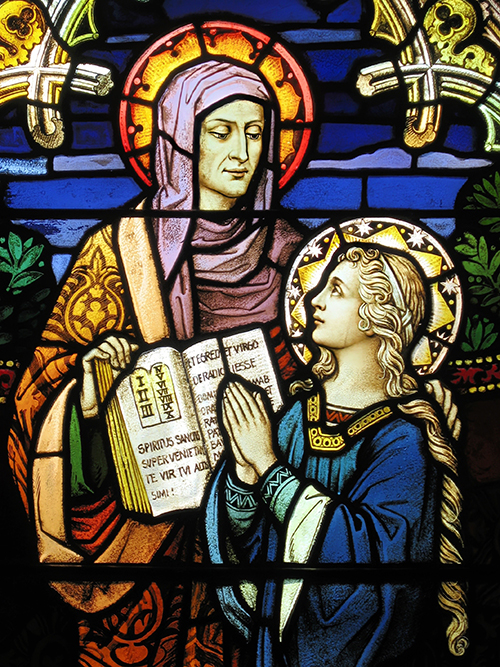

Now, back at school, Billy, Fr O’Grady from the Church had talked to the class about St Brendan’s Cathedral and had shown pictures of St Brendan’s Cathedral, which was here in this city, and so he asked his father whether they could go and have a look inside.

So off they went.

Now St Brendan’s was a very, very, very old cathedral, built when in some countries there was still kings and queens and princes and princesses and knights in armour and ladies in waiting.

Inside, the cathedral was dark, cold and kind of spooky.

Billy was a little bit scared, and a shiver ran through is body, so Billy held his father’s hand tight as they walked around.

The walls inside were very high, and right at the top there were stained glass windows all the way around.

Each window had a saint’s name.

Some Billy knew; St Patrick, of course, the twelve apostles, and St Brendan.

Others he had never heard of, like St Finbar, St Brigid and St Cairan.

As he walked around looking at all the windows, an amazing thing happened.

Outside, the clouds broke, and the sun streamed through the stained-glass windows, and suddenly the inside of the church was bathed in light.

Billy let go of his father’s hand and walked confidently on his own.

The following day at school, Fr O’Grady from the town Church came to the school to prepare the children for the coming feast of All Saints.

He began by asking the children, “Does anyone know what a saint is?”

Up shot Billy’s hand, and he waved it about with enthusiasm.

Fr O’Grady could not help but notice the enthusiastic waving, and besides, there was no other hand raised seeking the priest’s attention.

“Yes, Billy do you know what a saint is? Tell us now.”

“Father,” spoke Billy with confidence, “it is someone who lets the sun in and lights up the whole Church.”

(If you want to you may spell the word either sun or Son!!)