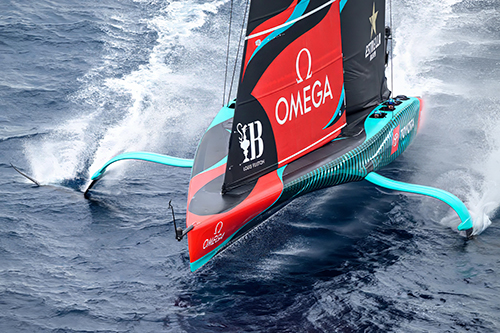

To observe an America’s Cup Yacht travelling at full speed is quite remarkable.

While practising for the America’s Cup held in Auckland in March 2021 the New Zealand boat, named Te Rehutai was seen regularly on the Hauraki Gulf.

My place of residence afforded me the opportunity to sit and watch these sailings.

When travelling at top speed, these yachts could reach speeds of upwards of 50 knots. This equates to about 92km per hour.

Consider this next time you are travelling in a motor vehicle.

There were occasions, however, when the yacht just sat in the water!

Becalmed because of a lack of wind.

No matter how sophisticated the shape of the hull or the sail design. No matter how quickly the onboard cyclists pedalled, without wind, the yacht went nowhere.

To enable the yacht to move, the sails catch the wind, and the force of the wind on the sails creates motion. This motion propels the yacht forward.

With the wind, the yacht is propelled forward at great speed. Without the wind, the yacht sits!

Ruah, (pronounced in Hebrew Ruach), is the Hebrew word translated as God’s Spirit. However, the word is also translated as breath, air, and wind in the Scriptures.

Today, Pentecost Sunday, is a celebration of God’s “ruah” – the breath, air, wind of God.

For those unfamiliar with yachting, it may be helpful to remember that you can only catch the wind if first you have moved your yacht from the safety of the yacht yard and ventured onto the water.

Second, you must unfurl the sails.

Third, you need to sit and wait for the wind to arise and then, in the words of the New Zealand poet Allen Curnow (1911 – 2001) become real,

“Simply by sailing in a new direction you could enlarge the world”