When I was living and in ministry in the city of Christchurch I had the use of a small car to get me from A to B and on occasions even as far as O and P!

The car was nifty and ran well and being small was easy to park.

However, as the driver, I noticed the car had a blind spot!

The framework of the chassis which held the left front window in place prevented me, as the driver, with a clear vision, from looking for oncoming motorists, cyclists and indeed pedestrians.

I found myself becoming concerned and frustrated.

Eventually, I took the vehicle to the dealership and explained what I considered a major manufacturing fault.

The gentleman listened attentively, and then we went and examined the vehicle.

To my surprise ( and chagrin), the gentleman sat in the driver’s seat, moved the seat forward a little and suggested I myself take the seat, and as it says quite simply in this Sunday’s Gospel, “ he was able to see!” ( Jn 9:7).

This Sunday, the Gospel is the story of a blind man receiving his sight.

The story in the Gospel involves spittle, dust from the ground forming a paste, washing in the pool of Siloam, a testy encounter with the Pharisees, and indeed disbelief.

All I needed to do was make a small adjustment to my sitting position!

However, while it was easily managed in the motor vehicle, in life, the shift maybe a little more difficult.

Where I sit and/or stand gives me a certain viewpoint; however, it may also provide a “blind spot”.

A blind spot is an obscuration of the visual field.

One could get all technical; however, from a medical point of view, it concerns the lack of light-detecting cells.

Perhaps from a Christian living viewpoint (or lack of!) if I sit or stand in the same place, I may in fact be preventing the light from penetrating, thus promoting a “blind spot”.

At the end of the Gospel, Jesus says, “ I came into this world, so that those who do not see, may see.” (Jn 9:39)

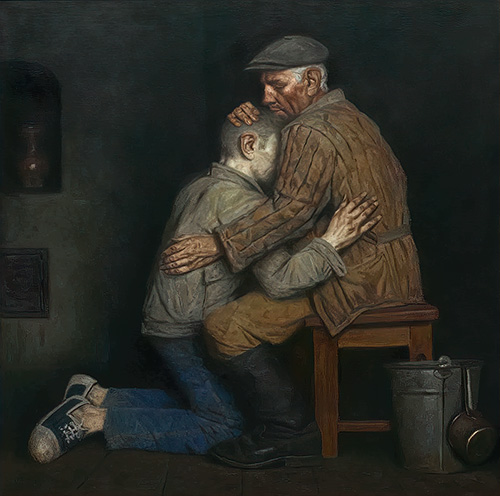

The illustration is a contemporary modern watercolour with the title, “Eyes Gazing”