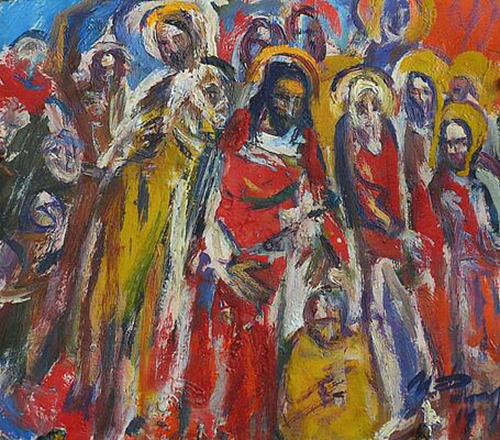

‘Then they came to Capernaum; and when he was in the house he asked them, “What were you arguing about on the way?” But they were silent, for on the way they had argued with one another who was the greatest.’ (vv. 33 – 34)

Imagine a room:

In the first corner there is a powerful dictator who rules a country.

His word commands armies and his shifting moods intimidate subordinates. He wields a brutal power.

In the second corner sits a gifted athlete at the peak of her physical prowess, a woman whose quickness and strength have few equals.

Her skills are a graceful power for which she is much admired and envied.

The third corner holds a rock star whose music and charisma can electrify an audience and fill a room with a soulful energy.

Her face is on billboards, and she is a household name. That’s still another kind of power.

Finally, we have too in the room a newborn, a baby, lying in its bassinet/crib, seemingly without any power or strength whatsoever, unable to even ask for what it needs.

Which of these is ultimately the most powerful?

The irony is that the baby ultimately wields the greatest power.

The athlete could crush it, the dictator could kill it, and the rock star could out-glow it in sheer dynamism, but the baby has a different kind of power.

We have a language we only use around babies (usually unintelligible to anyone!)

The radio and TV volume are dependent on the sleep pattern of the newborn, as is the time to start up the motor mower.

The baby can touch hearts in a way that a dictator, an athlete, or a rock star cannot.

Its innocent, wordless presence, without physical strength, can transform a room and a heart in a way that guns, muscle, and charisma cannot.

We watch our language and actions around a baby, less so around athletes and rock stars.

The powerlessness of a baby touches us at a deeper moral place.

And this is the way we find and experience God’s power here on earth, sometimes to our great frustration, and this is the way that Jesus was deemed powerful during his lifetime.

Jesus, standing wordless before Pilate might be the most power-filled moment in the entire Gospel story.

The entire Gospels make this clear, from beginning to end.

Jesus was born as a baby, powerless, and he died hanging helplessly on a cross with bystanders mocking his powerlessness.

Yet both his birth and his death manifest the kind of power upon which we can ultimately build our lives.

They are two moments which are still celebrated the world over.

The world stops at Christmas and Good Friday. Most shops are shut, public transport changes it schedules, usually meaning fewer services, and, maybe ironically, our Churches are most full!

When the Gospels speak of Jesus as “having great power” they use the Greek word, exousia, which might be best rendered as vulnerability.

Jesus’ real power was rooted in a certain vulnerability, like the powerlessness of a child.