In this Sunday’s First Reading there is the most beautiful imagery offered to us by the prophet Isaiah, namely, the image of the nursing mother! Isaiah writes:

“ Thus says the LORD:

Rejoice with Jerusalem and be glad because of her,

all you who love her;

exult, exult with her,

all you who were mourning over her!

Oh, that you may suck fully

of the milk of her comfort,

that you may nurse with delight

at her abundant breasts!

For thus says the LORD:

Lo, I will spread prosperity over Jerusalem like a river,

and the wealth of the nations like an overflowing torrent.

As nurslings, you shall be carried in her arms,

and fondled in her lap;

as a mother comforts her child,

so will I comfort you;

in Jerusalem you shall find your comfort” ( Is. 66: 10 -14c)

And, it is ‘the Lord’ who is offering us this image! Sit quietly with the images being offered, “that you may suck fully of the milk of comfort”; “that you may nurse with delight at her abundant breasts”; “as nurslings you shall be carried in her arms, and fondled in her lap”; “as a mother comforts her child, so I will comfort you.”

They are warm cuddly, nurturing, nourishing, secure images!

For most of us (and indeed I need acknowledge there are exceptions with what is known as latching on and/or sucking)), our first drink outside of the womb was from our mother’s breast – we did indeed ‘suck fully of the milk of comfort’, and nobody taught us! We were placed to our mother’s breast and we sucked! Is there something intuitive in the baby that has them suck?

The baby’s ‘latch’ is really the key to the whole process. A good latch will mean that the baby’s mouth, tongue and body as well as the mother’s nipple and breast are in the right position. The baby will need to open their mouth wide enough to allow the tongue to protrude forward, past the gum ridge and then take a big mouthful of the breast. Babies do not nipple feed, they breastfeed, which means that they need to have more than just the tip of the nipple in their mouth to transfer milk effectively. The baby’s tongue, lips and cheeks will form a seal on their mother’s breast tissue and their lips should be flanged outward.

I have been musing (trouble I know!), what a beautiful image for our relationship with our God, to place ourselves on the breast of our God and we will indeed suck and be nourished. Maybe we have become so sophisticated, so mature, so adult, that we have lost the ability to suck. Such a primal activity!

Might the essence of prayer be in fact ‘sucking on the breast’ of our God? I am placed on the breast of my God, and I will suck immediately!

Of the many books I own and have read concerning prayer, I have never known one to use the Isaiah image of “ sucking fully of the milk of comfort”. They are all about the right place, the right time, the right posture, the right breathing! Have we, in our sophistication lost the sense of when to feed? The baby knows intuitively when it is feeding time, namely when it is hungry!

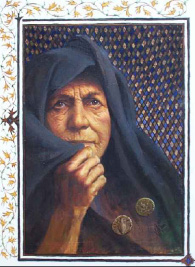

Julian of Norwich (1342-c.1416) is known to us almost only through her book, The Revelations of Divine Love, which is widely acknowledged as one of the great classics of the spiritual life. She is thought to have been the first woman to write a book in English which has survived. In this book she writes, “As truly as God is our Father, so truly is God our Mother” , and again, “when [a child] is hurt or frightened it runs to its mother for help as fast as it can; and [God] wants us to do the same, like a humble child, saying, “My kind Mother, my gracious Mother, my dearest Mother, take pity on me”‘ (trans. by Elizabeth Spearing, Julian of Norwich: Revelations of Divine Love (London: Penguin 1998), p. 144).

Am I hungry for “the milk of comfort” from Mother God?