Walking among the ruins of the ancient city of Ephesus (in Western Turkey) one is brought to a standstill by the site of the Library of Celsus.

Once a repository of over 12,000 scrolls and one of the most impressive buildings in the Roman Empire, today, only the library’s impressive facade remains of this once great building and is a silent witness to the city’s stature as a great centre of learning and early Christian scholarship during the Roman period.

As a part of the façade stood four statues.

Destroyed by fire in the 3rdC and by an earthquake in the 10thC, the facade was reassembled and then partially restored. The great statues of the building’s facade were taken to Vienna after their discovery and so today they have been replaced by faithful copies.

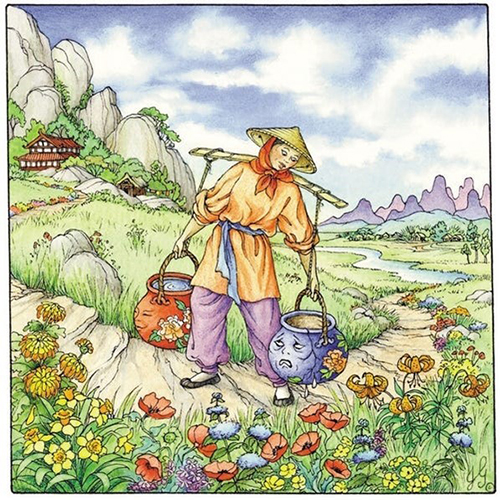

One of those statues is named Σοφία, Sophia.

Sophia, also spelled Sofia, is a feminine given name from the Greek for wisdom.

This word “ Σοφία” we encounter in our first reading this Sunday (Wis. 7:7 -11).

The reading contains the English word “her” no fewer than 10 times!

My dictionary describes “her” as ‘third person singular feminine dative pronoun’

For some reason we are fixated on the idea that God is essentially masculine, and we’ve tended to create our imagery around that fixation: God is Father, Warrior, or King.

However, our Scripture is filled with all sorts of imagery for God that is feminine: God is a mother bear, protecting her young; God is a mid-wife assisting in birth; God is a nursing mother giving sustenance; God is the Lady Wisdom, calling us to paths of justice and truth.

These images aren’t exclusive or exhaustive. They’re meant to engage our imaginations, to invite us into our own imagery, to help us find our own ways of experiencing God.

Wisdom offers an alternative. Wisdom calls us to consider a feminine posture. Wisdom calls us to bring compassion and generosity to our differences.

Wisdom invites us to see the world through feminine eyes rather than masculine, to allow our suffering to inform us.

For centuries the Church has talked about Trinity only with reference to the individuals who comprise it: Father, Son, Holy Spirit. That’s a masculine concern.

However, a closer reading of the theology of the Trinity has the Father “begetting” the Son, and the Son and the Father “begetting” the Spirit.

In the Nicene Creed we pray, “I believe in one Lord Jesus Christ, the Only Begotten Son of God, born of the Father before all ages.

They are in a “begetting” relationship, which sounds very feminine to me.

“Born of the Father” has imagery of childbirth!

The illustration is of the statue of Sophia – Wisdom, Celsus Library, Ephesus, Turkey.