I have written and stated on many occasions, “you cannot die nicely, or tidily nailed to a cross.” That is why the Romans used crucifixion as a means of inflicting the death penalty. If you are wearing a cross on a chain around your neck, or maybe pinned to your clothing; maybe you have one hanging on a bedroom or lounge wall. Have a close look – many worn round the neck have no figure, and many we hang on our wall and in our churches, while embodied, the body is of a dead Jesus, not a dying Jesus. Our profession of faith proclaims. “dying you destroyed our death”; it was Jesus dying on the Cross that effected this, not Jesus dead! You cannot die nicely through crucifixion – and that is precisely why the Romans chose the method. Golgotha was a rubbish dump and with Jewish strict laws on purity, what better place to set up crucifixion pylons. Jesus was stripped naked, again a huge insult to Jewish rules of purity – a grown man naked in public was reprehensible. Both actions, on their own, would have deterred family and close friends from gathering – the intention being that the person died in gruesome agony alone. I remember the brilliant lines of W.B.Yeats at the end of his poem ‘The Circus Animals’ Desertion’:

I must lie down where all the ladders start. In the foul rag-and-bone shop of the heart

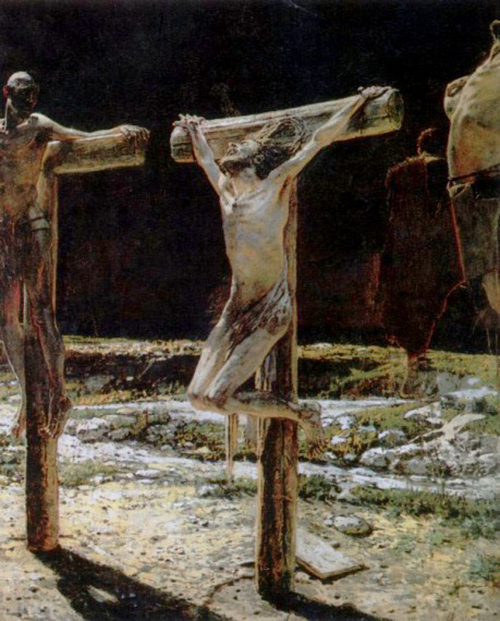

The artwork I have chosen is by the Russian realist painter Nikolai Ge (1831 – 1894). A copy hangs in Museum d’Orsay in Paris. The first version of the canvas was written in 1892, and the viewer is confronted with oppressive and hopeless emotions. Probably it is difficult to underestimate the hopelessness and complete despair of the last moments of the life of Jesus and his death, which, would have been unbearably painful. Nothing can be done when the body is nailed to the cross and hangs on it. Paying attention to the face, one can see how the death throes distorted the face and a death painful cry came from the mouth. Note, as symbolically and indifferently depicted, apparently one of the “executioners”, that in the background, having done their work, simply indifferently went about his business.

The work was considered shocking and near-blasphemous and Tsar Alexander ordered it to be withdrawn from the 22nd exhibition of the Itinerants where it was shown for the first time.

The poem is by the priest/poet Malcolm Guite, titled “Jesus Dies on the Cross

The dark nails pierce him and the sky turns black

We watch him as he labours to draw breath

He takes our breath away to give it back,

Return it to it’s birth through his slow death.

We hear him struggle breathing through the pain

Who once breathed out his spirit on the deep,

Who formed us when he mixed the dust with rain

And drew us into consciousness from sleep.

His spirit and his life he breathes in all

Mantles his world in his one atmosphere

And now he comes to breathe beneath the pall

Of our pollutions, draw our injured air

To cleanse it and renew. His final breath

Breathes us, and bears us through the gates of death