In virtually every culture there is, somewhere, the concept of having “to sit in the ashes for a time” as a necessary preparation for some deep joy or fulfilment.

For example, we see this in a story many of us will be familiar with from our childhood years: the story of Cinderella.

“Cinderella”, or “The Little Glass Slipper”, is a folk tale with thousands of variants throughout the world.

The protagonist is a young woman living in forsaken circumstances that are suddenly changed to remarkable fortune, with her ascension to the throne via marriage.

The story of Rhodopis, recounted by the Greek geographer Strabo sometime between around 7 BC and AD 23, about a Greek slave girl who marries the king of Egypt, is usually considered to be the earliest known variant of the Cinderella story.

The version that is now most widely known in the English-speaking world was published in French by Charles Perrault in 1697.

Another version was later published by the Brothers Grimm in their folk tale collection in 1812.

The name itself, Cinderella, holds the key: It is derived from two words: Cinders, meaning ashes; and Puella, the Latin word for young girl.

In the Perrault edition we read, “When she had done her work, she used to go to the chimney-corner, and sit down there in the cinders and ashes, which caused her to be called Cinderella”

Etymologically, Cinderella means the eternal girl who sits in the ashes, with the further idea that before she, or anyone else, gets to put on the royal clothes, go to the ball, and dance with the prince, she must first spend some time sitting in the ashes, tasting some emptiness, feeling some powerlessness, and trusting that this deprivation and humiliation is necessary to help bring about the maturity needed to do the royal dance.

Fairy tales are recognised as archetypal.

An archetype is a character, idea, symbol, setting, situation, or challenge that reflects a universal human condition that is recognisable to anyone from any culture or place around the globe because of its universality.

So, in any fairy tale, we have hero and heroine, prince and princess, wise man and crone, wizard and witches, villains and knights in shining armour. We have wicked stepmothers and fairy godmothers, dark forests and wide rivers.

In this Sunday’s Gospel (Luke 4: 1 – 13 ) we have a rich image something similar to “ sitting in the ashes”.

The image is one of the richest images that flows through our holy book, the Bible.

The image is of the desert; of Jesus going into the desert voluntarily to fast and pray.

Scripture tells us that Jesus went into the desert for forty days and, while there, he ate nothing.

This doesn’t necessarily mean that, literally, he took no food or water during that time.

Rather he deprived himself of all physical supports (including food, water, enjoyments, distractions) that protected him from feeling, full force, his vulnerability, dependence, and need to surrender in deeper trust to God.

And in doing this, we are told, he found himself hungry and consequently vulnerable to temptations from the devil – but also, by that same token, more open to God.

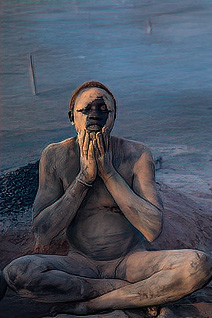

The desert, by taking away the securities and protections of ordinary life, strips us bare and leaves us naked, both before God and the devil, and indeed our very selves.

This brings us face-to-face with our own chaos.

That’s an image for Lent.

Each of us is invited to that quiet space where we can ‘sit among the ashes’ and be fed with what, in the first instance appears to be the remains, the residue, the detritus – and just what might be the most nutritious, the most nourishing, the most sustaining.

The journey of Jesus into the desert is archetypal.